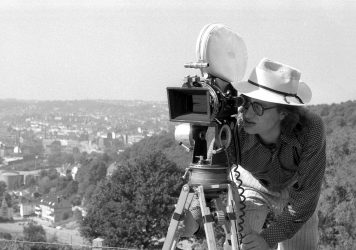

At the beginning of his 1985 documentary Tokyo Ga, made due to a production delay in his then-forthcoming fiction feature Paris, Texas, Wim Wenders speaks of his desire to capture the distinct pastel hues of the Tokyo landscape. Ever the aesthete, he tries to make sure he has the correct cameras and lenses for this particular job, and the film documents how he takes inspiration from the laconic, precise work of the late, very great filmmaker, Yasujiro Ozu, in achieving his aims.

It is in this context that Wenders’ new, Oscar-nominated feature, Perfect Days, plays out, a wistful examination of society and culture as presented through the lens of an easygoing public toilet cleaner. As with the ironically-titled Lou Reed song with which it (almost) shares its name, it’s a film about happiness as an elusive ideal that is inextricably tied to sadness, loss, regret and pain, but something that’s still very much worth striving for.

Just as the filmmaker’s work is pockmarked with his own personal, sometimes intriguing and esoteric passions, Perfect Days is about not just appreciating, but losing ourselves in the everyday minutiae around us. Wenders’ camera imbues the small things we take for granted – including visiting the restroom – with a sense of the miraculous.

Wenders’ global peregrinations have been thoroughly documented in the films he has made, a reflection of the fact that his production company, established in 1976 and still truckin’, is famously called Road Movies. And while he harbours a deep fascination for places such as Berlin or the American South, his cinematic obsession with Ozu lends Tokyo a certain emotional import within his oeuvre. Much like its director’s yen for looking beyond cultural borders, Perfect Days is a film about a man named Harayama (Koji Yakusho) whose cultural fixations geographically straddle both his hometown (collecting and cultivating Bonsai trees), and the United States (collecting classic American rock albums on tape, watching baseball, reading William Faulkner novels).

In Tokyo Ga, Wenders approaches his film with referential fascination for the country and its people. Like all good documentaries, it is a lovably rambling chronicle of the research process rather than an encapsulation of a pre-ordained thesis. There’s a slight anthropological bent to it, in the way the filmmaker wants to tease out the things that make Japanese culture unique from the rest of the world, such as its busy Pachinko parlours, its love of wax food models, or an obsession bringing cutting-edge technology to even the most banal domestic chores.

On the evidence of Perfect Days, one can detect that Wenders now has a clearer sense of the lay of the land. His depiction of the landscape and his emphasis on certain details is now a little more muted and focused. He is no longer a stranger in a strange land, a cine-tourist who is soaking up and processing an overwhelming barrage of sensual stigma. This is the other side of Tokyo, one that the cameras (certainly those being clutched by Western hands) depict much less often than usual.

It is possible to chart the evolution between the more wide-eyed Wim of Tokyo Ga and the more circumspect Wim of Perfect Days. Tokyo was one of many stops in his globe-trotting sci-fi folly, Until the End of the World, from 1991. For a relatively short 15-minute segment (part of the film’s epic five-hour runtime), he stages a screwball shoot-out in one of the city’s famed capsule hotels. As with Tokyo Ga, he selects this particular location, with its cantankerous salarymen attempting to nap, as an example of one of the city’s more eccentric innovations, and it feels a little as if the director is still trapped in his exoticising tourist mode.

But the real gateway through to Perfect Days is Wenders’ 2009 photography exhibition, Journey to Onomichi, in which he pays direct homage to his favourite film of all time: Ozu’s Tokyo Story. The show and accompanying book chart his visit to the sleepy seaside town where the majority of Tokyo Story takes place, and while it’s possible to see the architecture of the 1950s in the images, you have to see it through a process of modernisation and industrialisation. Just as Ozu told a story of bittersweet generational rifts and the melancholy of time passing, so does Wenders in Perfect Days show a world – and social attitudes – from yesteryear just bubbling beneath the shiny surface.

Perfect Days is released in UK cinemas on February 23. Find screenings and book tickets at mubi.com/perfectdays

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 22 Feb 2024

The German multi-hyphenate on how he’s future-proofing classics like Wings of Desire and Paris, Texas.

Wim Wenders' gentle character studies features a beautifully restrained performance from Kôji Yakusho, as a toilet cleaner who lives a simple life in Tokyo.

At the revamped Tokyo International Film Festival, the spotlight shone brightly on upcoming Japanese artistic voices.