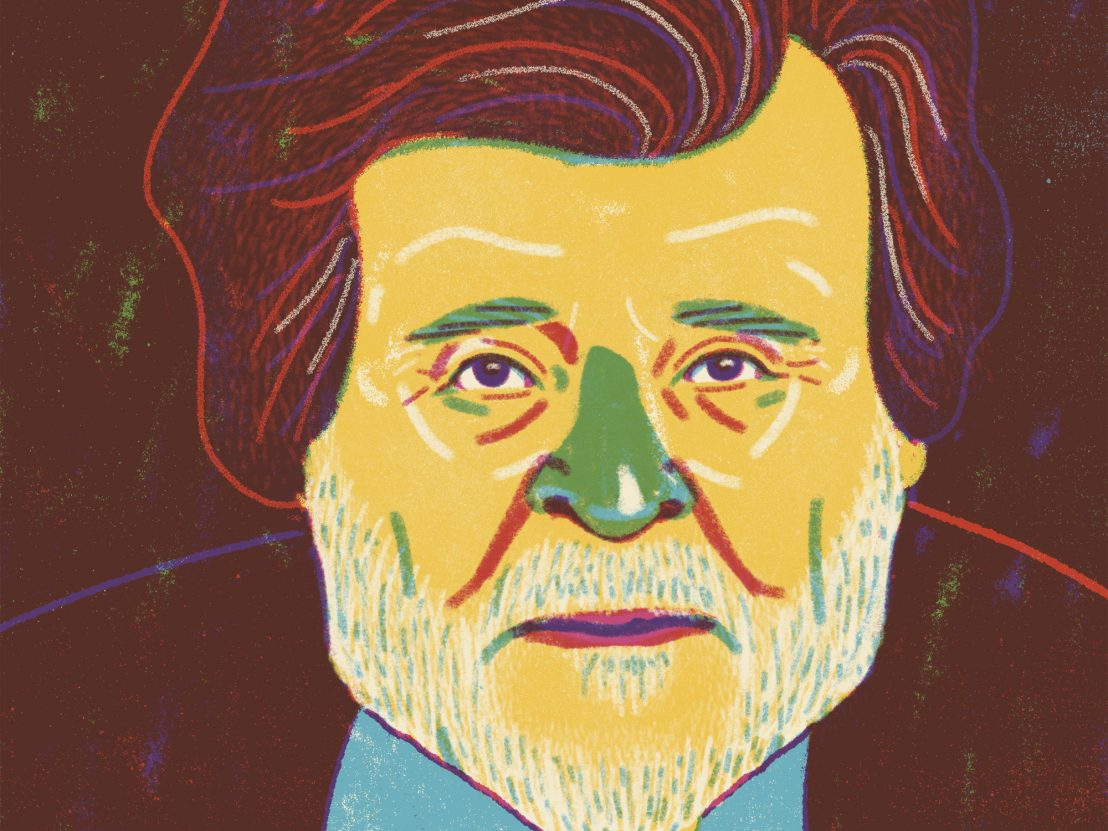

On the occasion of his highly anticipated and long-awaited fourth feature film, we receive an audience with the master of Spanish cinema, who reflects on the long journey that Close Your Eyes had.

It has been 31 years since we last saw a feature film by the Spanish maestro Victor Erice, and that film was the transcendent documentary the ephemeral nature of art, The Quince Tree Sun. He remains most well know for his 1973 debut, The Spirit of the Beehive, about a young girl’s transformative encounter with cinema, and he followed it up in 1983 with a melancholy study of an emotionally estranged father and daughter in The South. Close Your Eyes is a scintillating and unspeakably powerful addition to this small but perfectly formed corpus of films, telling of a filmmaker attempting to find the missing actor who strayed from his incomplete final film.

LWLies: When you started working on the script for this film, did the story derive from an image, an object, or something else?

Erice: The idea for Close Your Eyes was generated by the memory of my film The South, and from the frustration that came from it being unfinished [due to budgetary restrictions, Erice was only able to make half of the proposed feature]. What this new film talks about is another unfinished film as well as the whole idea of “unfinishedness” and what that means in art and life. I always had this idea floating around in my mind, but Close Your Eyes only really took shape when I concocted the character of the director. The origin, then, is not an image or an object, but a very personal experience.

Close Your Eyes addresses the idea of an artist looking back at the work he’s made. Can you talk a little bit about your relationship to your own films.

With cinema, I maintain a relationship that I would describe as ‘existential’. What that means is that cinema, for me, is everything. It’s not just a professional occupation. But this idea of the existential concerns all aspects of cinema: my work as writer and director of the film; my enjoyment as a spectator; my analysis of the cinema I see; as a teacher in workshops. It’s total. I may be called a pedant for saying this, but Jorge Luis Borges was once asked, ‘What is literature?’ and he responded, ‘It’s a form of destiny.’ I don’t know whether I can simply adopt that stance, but that is what I feel: cinema is a form of destiny.

When did you first develop this idea of cinema as this all-enveloping thing?

To answer this we should go back to the origin. The first time I went to the cinema I was five-and-a-half years old. It was a revelation. I had an experience that was exactly the same as Ana in The Spirit of the Beehive. It was an experience of horror; of complete terror. The film I watched wasn’t James Whale’s Frankenstein, it was Roy William Neill’s The Scarlet Claw from 1944, a Sherlock Holmes film, but it was a very similar experience. I documented all of this in my short film La Morte Rouge. So we’re talking about 1946, it was postwar Europe, and the landscape was in a complete state of ruin. I could see in my country and in the streets of my city the direct consequences of this horror. And it wasn’t just the Spanish Civil War, but World War Two as well.

The Scarlet Claw, a fictional work, just took me to reality. I could see the continuity, the relationship between film and the suffering and desolation that was present in the streets. In that film, people dressed like people in my city. If it had been a film set in the Roman Empire and the actors were wearing period costume, maybe I wouldn’t have felt such a strong connection, but because it was so real I felt it straight away. Also of note is that the murderer in the film was a postman, and he dressed exactly like the postmen in my town. So whenever the postman came, I would hide in the corner. For me, cinema was an introduction to reality. All my films have a history of something that happened in reality.

This idea of young people having this revelatory experience with cinema in The Spirit of the Beehive and La Morte Rouge is reversed in Close Your Eyes, as this revelation occurs closer to the end and to someone much older.

The question that I leave in the end of Close Your Eyes, where blood ties and friendship haven’t been able to revive a person’s lost memory: is that something that a film can do? That is the challenge. And there will be many answers to this question; as many answers, in fact, as there are spectators. A key element is that there are moments where actors look directly into the camera. What I wanted was for the actors to be looking at the spectators. I want to create a dialogue with the audience. The debate, then, is has the daughter failed in bringing back her father’s memory? Has the best friend failed also? For an actor, is it much more important to have one film that helps to fill in the blanks? We know how actors live their lives. Going back to La Morte Rouge, this murderer postman is an actor who dressed up as a postman, so the film is about this question: what can an actor be? For me, that’s fundamental.

You show that Miguel, the director character, has once written a book about historical ruins which he re-discovers in a book shop. Do you have a personal interest in the exploration of the past?

The truth is that for this film I’ve had to use a convention that is used in thrillers. Discovering something that happens that is unknown, and thus being inspired to take a journey. And I used this device consciously, to get more financial support. My previous film, The Quince Tree Sun, was very radical: it had no actors, had no script whatsoever, but it was a really modest production. But for this film I needed a lot more financial support; I had to go through the various TV stations, the ministry of culture, and I had to play their game. And as such, they wanted to see a script in advance. And so it’s the same as someone like Pedro Costa – we both used to work outside of the system. And with this film, I am inside the system. And it’s the concession I had to make to be able to talk to people again. The challenge for me in this film was how to move from the idea of the enigma – which is something that’s missing – to the mystery – which is something unanswered and beguiling. This is a strategy to get funding. A friend of mine jokingly said that by doing this I was entering ‘enemy territory’.

And yet it feels like it’s unmistakably like a Victor Erice film. One aspect that is different is the digital aesthetic.

I’ve worked with digital before. And actually in this film there is a bit where I work with film, in the making of the apocryphal film-within-a-film, The Farewell Gaze. My opinion about digital is that it has given us this unprecedented opportunity to control images, and this is extraordinary. But it’s also a fundamental change to the language and grammar of cinema. Now, we’re not capturing images as the Lumière brothers originally intended; now we are manufacturing images. We’re in this place of absolute abstraction where even artificial intelligence may one day be able to make a film. For me what is clear is that digital cinema is not an audio-visual medium. It’s not the same as film. Audiovisual is not cinema any more, and I’m quite clear about this. It’s not about capturing light and sound. That is to say, we, the filmmakers, are not changing the world in front of the camera, but we are changing the image we capture of the world from behind the camera. For me, this is a terrible loss for artists everywhere.

How much digital manipulation did you partake in with this film?

None. Some slight light correction, but practically no post-production. With digital images it’s about calculation. The director of photography doesn’t need to make the same practical calculations and measurements that they once did. Now what a director of photography needs is a good colourist – someone who can manipulate the image. From the time of the Lumière brothers – and I’m not coming from a romantic point of view, I’m not nostalgic for this era – the only thing that’s left is the cinemas themselves. But the places where spectators go to watch films are also disappearing. Now people watch film on TV, computers and mobile phones. The true place to watch a film is in the cinema. But the big corporations are getting rid of them. I think they should be kept. It draws me back to the middle-ages where poetry was spoken in public rooms or squares, and I see cinemas as serving a similar function. When I was a child, seeing a film meant being out of the house, with my family, with my friends, socialising. It is possible that cinemas are residual now, and that’s what happening. It’s an anthropological change.

Is Close Your Eyes your last film?

Some critics have referred to it as my ‘swansong’, but I’m resisting that as it means my destiny is a cemetery, and I want more than that.

Published 8 Apr 2024

The legendary Spanish filmmaker returns with his first feature film in 32 years, which centres on the strange case of an actor who disappeared under mysterious circumstances.

Every inch of every frame in this lilting father-daughter drama by Victor Erice is calculated perfection.